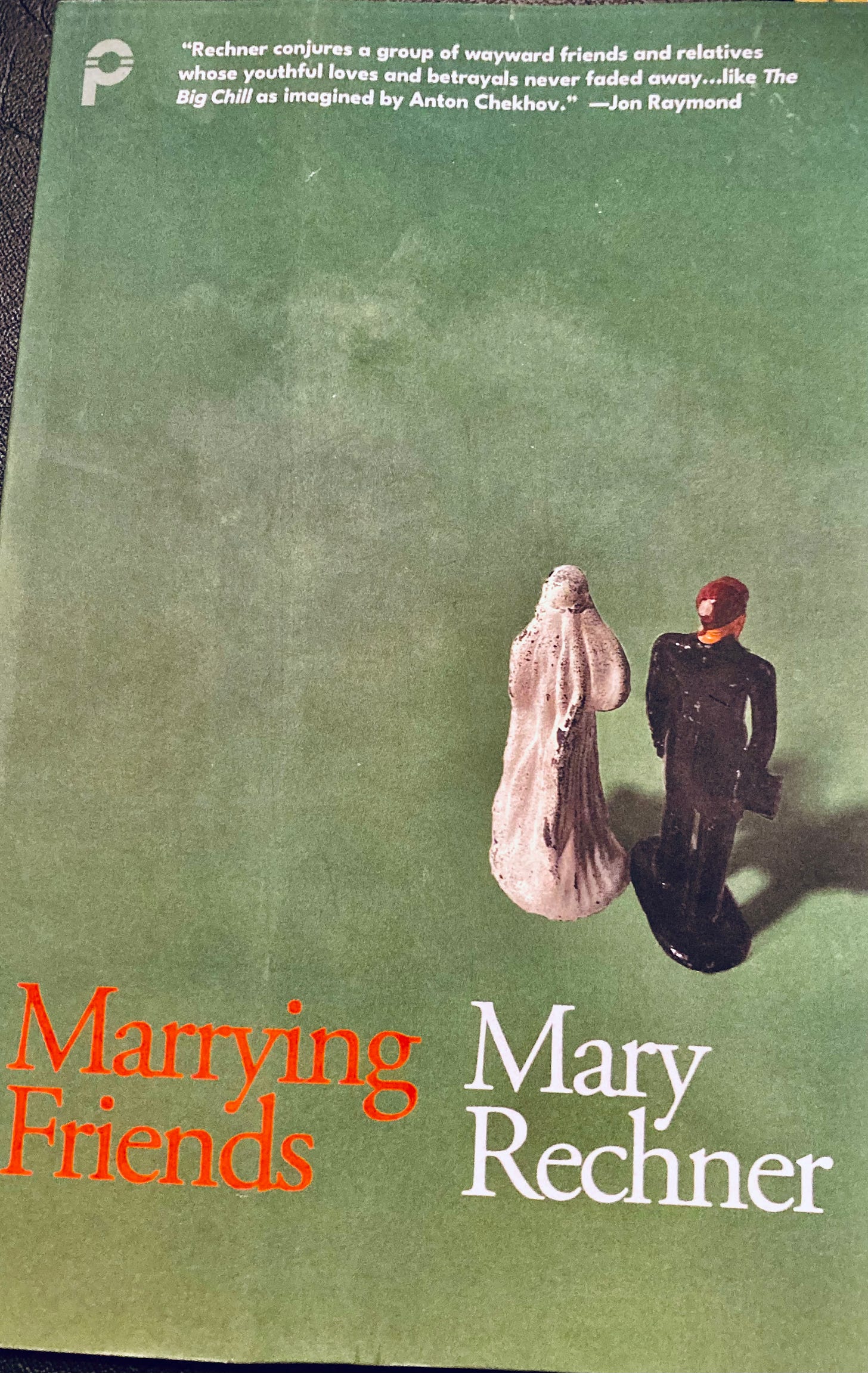

Marrying Friends by Mary Rechner: sort of a review

John Carr Walker Sitting In His Little Room No. 101

When I began writing this, I didn’t know if I should call Mary Rechner’s Marrying Friends a collection of connected stories or a novel-in-stories, or if there was a worthwhile difference. I did know that what seemed to matter to Rechner also mattered to me. Stories matter, their organization, modesty, and limitations, as well as all the messy life that surrounds a story. The mess tries to get in—it weeps around the window sash and rattles the door on its hinges—but the firm structure of story keeps the mess out. I love that about short stories. They are little ships at sea that insist the vessel matters more than the raging storm. In this John Carr Walker Sitting In His Little Room, I’ll consider how the stories in Marrying Friends stay dry—stay stories—even as the sea-swells rise and the waves crash down.

When I talk about story, I tend to mean two things. First, I mean story as the word is widely understood, as event, as in what happens? Second, I mean form, as in the short story, the tale, the fable, or the parable. Whatever the form, a story told short demands focus, clear emphasis, and an almost obsessive attention paid to one or two people, places, struggles, desires, and so on. For me, that necessary obsession is the short story’s great draw, and why I prefer the story to the novel. E.L. Doctorow refers to the novel as a “kitchen sink form.” In other words, everything and anything can come inside, can become part of “the world-building,” to borrow a garish phrase. Novels are messy. Where the novel is wide open, the story is buttoned tight. In fact, that’s probably why I prefer the story. I also prefer small, smelly hotel rooms to nice campsites. I prefer the indoors to the out. Give me a cramped corner over a rolling meadow any day.

Which makes a book like Marrying Friends a potentially confusing clash, for me, between the in and the out, the shelter and the storm, the short and the long. Marrying Friends is made up of fourteen stories, yet the stories come together to tell a bigger story about what happens to a group of friends and family after the unexpected death of Mark: husband, son, father, friend. In each story, Rechner focuses on (or obsesses over) a particular character and her struggle. But the struggle—knowing a secret, concealing a kind of grief, the high-wire act of smiling sympathetically while holding one’s tongue, or not—always connects to Mark’s death and his complicated web of family, friends, and lovers. The same storm raging outside tests the weatherstripping of each story, so to speak. The storm beats and batters and threatens to break through my comfortable, comforting shelter. The novel is throwing everything and the kitchen sink at the story, yet Rechner’s stories stand strong. The stories don’t become chapters. Marrying Friends isn’t a novel with stories for guardrails. Rather, Rechner uses the story’s great strengths—taut structure, interior concerns, close-up focus—to dramatize the plight of individuals who are also the friends and family of others. Taken together, those parents and in-laws, siblings and besties, partners and crushes and affairs, become the novelistic storms raging away at the individual.

Connected collections, or novels-in-stories—whatever—tend to fall in two big camps. There’s the camp that turns the the connections between stories into a puzzle. Huge casts of characters, a wide variety of voices, narrators, and perspectives, often informed by a wide variety of times and places, and lots of titles on the table of contents page. Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Good Squad is a recent, famous example from the puzzle camp. (Other Electricities by Ander Monson is an older, less famous example, which I mention here because it’s great and should be better known.) In this style of collection, the story form is a compact, contained way to shape the fragments of a fractured narrative. That fracturing, however, is the main structural thrust. The story becomes a solution to the problems of fracturing, a sort of formal convenience, rather than a driver of narrative. I usually spend too much time flipping back to earlier stories, trying to remind myself where I’ve seen this character before, or when that similar (or identical) action occurred. It can be fun, at first, but usually ends up exhausting me. I’m never sure if the author intended to send me on a shadow choose-your-own adventure, or if I’m expected to read more closely, remember more, take notes. I didn’t finish A Visit From the Good Squad for this reason. I grew weary of constructing the narrative for myself, and that construction work eventually smothered my investment in characters and their emotional stakes. (On the other hand, I’ve read Other Electricities several times, and it’s more fractured than Goon Squad, so who knows what the takeaway should be.)

Marrying Friends belongs to the other school of interconnected story, in which the connections flow through the same channels over and over again. Instead of scattering the reader’s attention with a fractured narrative, Rechner keeps coming back to a single explosive event—Mark’s death—and employs the story form to show us different characters’ reactions to death, loss, guilt. More importantly, Rechner uses the story form as a way to share secrets with readers. Characters don’t necessarily tell their secrets to other characters, so the interiority of the story becomes intimate. The intimacy grows with each story, as the web of connection expands, as we’re reminded of the secrets characters share, and more powerfully, the secrets they do not.

At first, the connections between stories and characters are made obvious. They follow the logic of chronology and spatial relationship. A secondary character in the first story becomes the primary character in the second story. Rechner doesn’t ask her readers to remember too much for too long. Instead of assembling a jigsaw puzzle, we’re stacking blocks. In the second half of the collection, the connections span greater distances, and are stretched thinner, but by now I know the characters well enough that I recognize them by behavior as well as by name. By building these connections in partnership with the reader, Rechner allows us the bandwidth to respond emotionally to her characters. I feel the isolation and the tentative alliances, forged through keeping or sharing secrets about Mark, within the close confines of story. I feel the force of those secrets pushing and pulling across the stories, creating a novelistic storm, out there, in a wider world. That wide world matters to the story as event, but not to the story as form. I think that balance is beautiful.

I admire the deft, space-saving maneuvers short story writers make in pursuit of impact. I miss that in novels. In Marrying Friends, Mary Rechner feeds the short story nerd in me by keeping to the form. And yet, by attending to the events of stories, Mark’s death accumulates texture, shade, and meaning, novelistic details that transcend each story without obscuring form. I still don’t know if I should call the book a novel-in-stories or a collection of connected stories, but I don’t think it matters. It’s a great story, and it’s a great book of stories. What else is there?