Screening

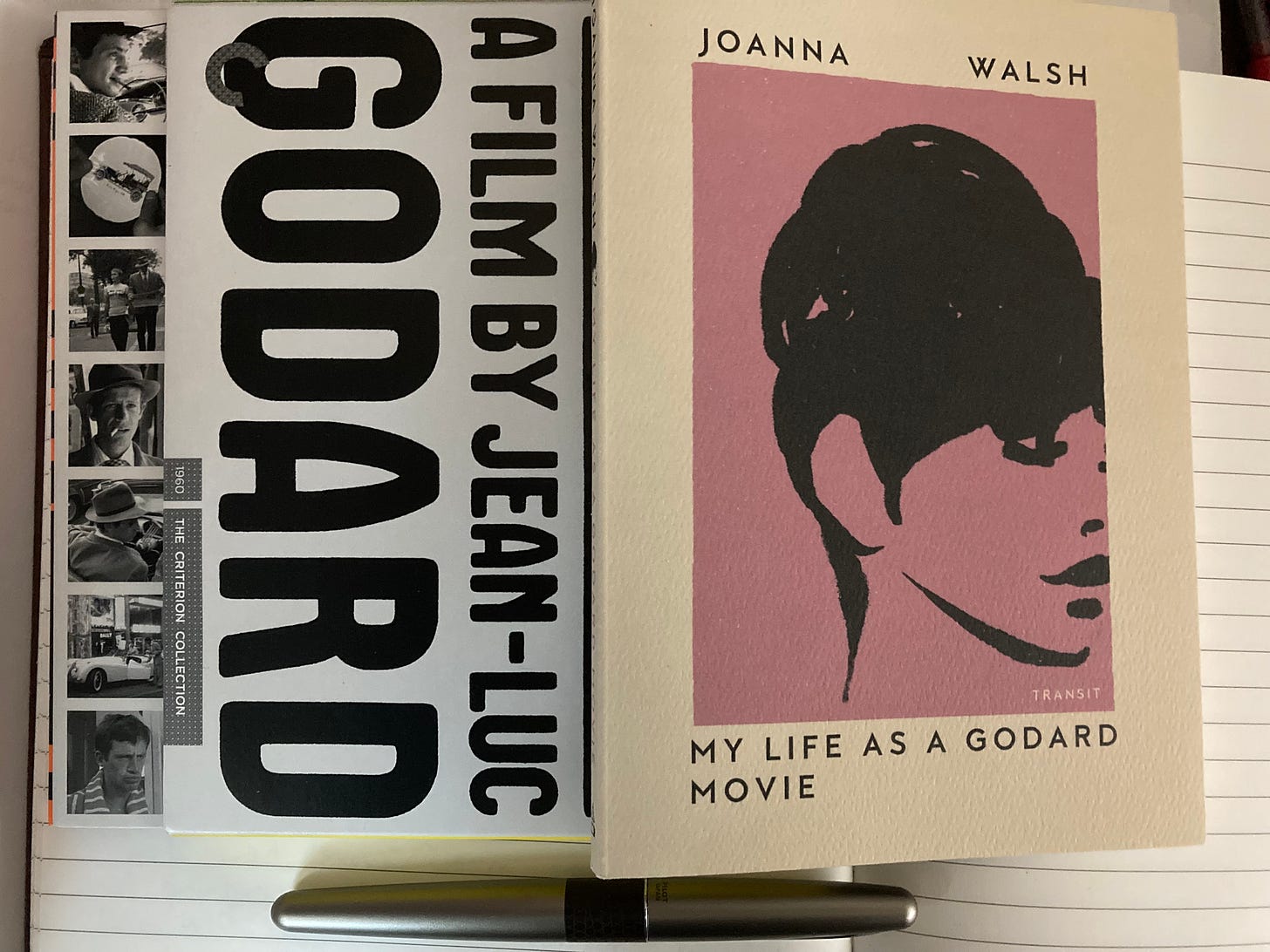

Joanna Walsh's My Life as a Godard Movie is difficult to describe, harder to introduce. It would be easiest for you just to go read it, save me trying to bumble my way through explanations, because I suspect it's a work that chameleons to whoever's reading. Your personal experiences with French cinema and beauty, whatever that means to you, may well determine your view of Walsh's text, which has a way of changing its colors. The exception to such change is the fact My Life as a Godard Movie is staunchly about being a woman, living in a world that would rather look at than listen to women, rather pedestal-ize women than have them participate in life as independent players.

Joanna Walsh considers her own experiences as woman by thinking about the New Wave films of Jean Luc Godard, an auteur capable of listening to women, and of giving women characters agency, as well as treating women like mannequins, beautifully dressed and perfectly proportioned, without a voice or thought of their own. Walsh wonders aloud on the page about Godard's intentions, if he's another man fulfilling a patriarchal stereotype through his art, or a visionary showing us how society punishes women. And if the latter is true, Walsh asks, why doesn't Godard have vision enough to see another role for women in his films? Is there a glimmer of another way?

I'm familiar with most of the Godard films Walsh considers. And I'm a cis man. Reading Walsh, I realize that, at least at times, she and I could be watching different films. What I see in a scene or a shot Walsh reframes in her own gaze, and asks me to look again with benefit of her insights. This is what I mean when I say the book chameleons to the reader. Although My Life as a Godard Movie belongs to a series called Undelivered Lectures (published by Transit Books), it is not a lecture, but an invitation to learn, a kind of study session with your smartest classmate, an opening of stuck windows and airing of musty old rooms. And I love it.

Streeting

In an interview, Joanna Walsh described My Life as a Godard Movie as a pandemic project. Which instantly re-contextualizes for me the act of considering real life through the watching of films. For most of 2020, film is what we had, and for an awful lot of us, screens provided our only view of the great wide world. I had my own pandemic writing projects, all of which went looking for experiences in screens. My reading of Walsh changes slightly knowing the pandemic context: her consideration of Godard, and the act of looking for herself on his screens, becomes more urgent, and more vital, because mortality's at stake. Reading Walsh a few years after the end of social distancing, I remember my own suddenly necessary connection to screens, and being aware of the connection that formed across distances through screens. I remember watching myself watching. I wrote down some of my socio-critical thoughts about Zoom meetings while on Zoom meetings. Walsh articulates some of the same feelings.

Which makes Joanna Walsh's secret trip to Paris a thrill. It's told as confession, a flashback in stage whisper, about that time she took the new Eurostar train to Paris but told people she was at work working late. Instead she walked "tracing Paris's borders—west, then north, crossed the river, found the hill, walked without stopping for eight hours til...I took the train back to London." The escape saved her life, writes Walsh. I know what she means. Even though the trip happens decades before Coronavirus, it's a memory delivered to the reader in context of the pandemic, and therefore seems to save the writer from watching screens all day, a kind of close-your-eyes-and-see memory. It reinvigorates her connection to Godard, this tactile, personal memory, which also serves to reinvigorate her reader. It gave me a new, different way to feel about Walsh and her text. It also adds profound weight to the phrase Walsh writes a few chapters later: "I don't think this lockdown will ever end."

Considering

Locating My Life as a Godard Movie in the literary landscape is easier than describing the book's singular achievement. Essays on art, in which the act of the essayist considering becomes part of the text, the personal chasing and retreating from the intellectual as if in waves, goes back to Montaigne and the birth of the personal essay. Lamb, Hazlitt, and de Quincy all try their hand. So does D.H. Lawrence at the dawn of modernism. Geoff Dyer continues the tradition.

As so often seems the case, women writers must fight harder for their place in the landscape, and therefore, their population is smaller compared to the population of, you know, the world. Susan Sontag and Fran Lebowitz spring to mind, but I confess, I would need the internet to remind me of, or teach me about, other women writers living and working this particular land.

Coming to our immediate moment, I know Alice Bolin's Dead Girls: Essays on Surviving an American Obsession and Carina Chocano's You Play the Girl: On Playboy Bunnies, Stepford Wives, Train Wrecks, and other Mixed Messages to be insightful, piercing looks at the portrayal of women in media, and particularly on screens. Yet neither seem exactly contemporary to, or in complete harmony with, My Life as a Godard Movie. For one thing, Walsh's book was written during and published on the heels of a global pandemic, which feels to me like the newest update to literature; Chocano and Bolin's books, though published in 2017 and 2018, feel by comparison from another time. More important, however, is the choice of subject matter itself. Chocano and Bolin consider icons of popular culture, commercial art, and commerce itself, while Walsh focuses her attention on the arty, and at least by comparison, esoteric and highbrow.

Godard films were considered artistic statements from the time they were made, and therefore above the grubby concerns of commerce and fame for fame's sake—whether that's true or not, I don't know, but that was and is the perception. Godard's cultural reputation has only grown in the decades since his New Wave films were shot and first screened. Walsh need not make a case for their merit. She must also be more nuanced, subtle, and indeed, more personal, in her consideration. My Life as a Godard Movie isn't a takedown, nor a call for seriousness.

So what is it? What does Walsh finally see looking at Godard films? To end on her line: "What do I really look like? I don't know."