On The Spectrum With Stillness and Movement in L'Eclisse

John Carr Walker Sitting In His Little Room No. 132

1. Vittoria

Monica Vitti paces the apartment. As Vittoria in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1962 film L’Eclisse, she lifts a blind and looks out the window. The new, strange, EUR district of Rome offers little relief from stillness. Il Fungo tower looks like a mushroom cloud cased in concrete, a disaster captured, paused. The blind falls and she turns back to the room. A fan blowing creates the only movement, though the movement of a fan is hardly natural. The artificial breeze makes her lover’s tie twist a little. His pose in an armchair, like his vacant stare, is otherwise sapped of life, the picture of a clay figure without the full form of a statue. Like the Il Fungo tower, he too has been captured, and he’s not been carved to resemble a hero of old. Vittoria’s had it with him, his apartment, his blowing fan that passes for blood in his veins. Her pacing is prelude to walking out. Which she finally does. The film’s only a few minutes in.

We eventually learn that Vittoria and her lover Riccardo, played by Francisco Rabal, had been up all night discussing the end of their affair. Yet we sense this without being told. The long night crackles in Vittoria’s pacing, in her few lines of dialogue, and in her furtive looks out the window. She wants out. She needs out. It’s only stillness keeping her here.

Riccardo attempts to follow her. Physically speaking, he does follow her, first in his car, and later on foot through a park, but his movement comes too late, and feels to me as thin as the air through his fan, like the function of a switch, controlled and predictable, even though it’s electricity that makes the blades turn—we recognize something’s been turned on, but don’t feel any shock or sizzle from the current. Before he was silent, but he’s speaking now, and speaks louder and faster as the echoes lengthen. Outside Vittoria’s walk-up apartment, Riccardo recognizes the end. No goodbyes, we’ll call each other, he says.

We will hear Riccardo’s name a few more times in the film, but see him only once, outside Vittoria’s window, throwing pebbles at the glass, calling her name. She too sees him, but hides.

2. Piero

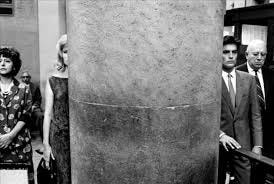

Alain Delon can’t sit still. He plays Piero, a young stockbroker, entirely in his element amidst the chaos of the Rome exchange. He only stops speaking to eavesdrop. He shouts, runs, and points as if he commands the lightning, or is lightning. Today, he gets lucky, and makes a fortune for Vittoria’s mother, played by Lilla Brignone. He’s heard about Vittoria, but has never met her till now. In the next shot, a column divides them, and while Piero stands confidently, Vittoria peeks out from her side, half-hidden by the architecture. We can already see where this is going.

Vittoria’s tendency to reveal only part of herself will soon irritate Piero because he, like the audience, believes that he’s exactly what she wants, even what she needs. The trapped, pacing woman who finally left her lover in the first act should fall madly in love with the guy who can’t sit still by the end of act two, right? And yet, she’s evasive, withholding, or simply uninterested. In the same way we understood Vittoria’s desire to leave Riccardo, we understand Piero’s confusion. I wish I loved you less, Vittoria tells him, or much, much more. This is closest to an explanation we’ll get from Michelangelo Antonioni for what happens next.

For a short while—for one afternoon, at least—Piero and Vittoria seem happy together, touching, laughing, making plans. They’ll meet tonight in their usual place, they say, and then tomorrow, and again the day after that, and son on. They embrace passionately—passion of some kind—before finally parting. Then begins L’Eclisse’s most famous sequence. The usual place, at the appointed meeting time, is deserted. Through a series of images—of landscape, architecture, and the gazes of strangers, of busses arriving and departing, the streets emptying of life and light—we understand it’s over between Piero and Vittoria. They mutually stand one another up. Perhaps the anxieties, excesses, and withdrawals of that time and place simply smother an affair between the likes of a Vittoria and a Piero. We don’t know for certain. Antonioni’s ending is powerfully, deliciously ambiguous.

3. What They Want

As enamored as I am with the end of L’Eclisse, I find an earlier sequence more telling. Vittoria accompanies her friend Anita on a trip in a small plane. The cabin is cramped so Anita and Vittoria get pushed together in the back seat. Vittoria’s delighted by what she sees outside: distant mountains, the checkerboard ground, the vast sky and clouds. At first, we see Anita’s amusement watching her friend gush, but gradually the camera zooms closer until the picture frames Vittoria alone. The previous dialogue, shouted over the noise of the engine, drops away until we have only Vittoria’s questions, exclamations, and laughter. Cinematically speaking, she’s by herself.

Her solitude continues once back on the ground. She strays from the group, wandering the airfield, watching planes overhead come in for a landing and taxi down the runway. At one point she wanders in to a commissary where someone tends bar and a few others drink and read newspapers, but Vittoria only stands in the doorway, and lingers there, as if deciding whether or not to break her solitude. The delight and wonder she experienced in the plane still lives in her, an afterglow in her smile and as a kind of aura in her distracted, daydreaming gaze. She looks at the people in the commissary and decides not join them. A moment later, Anita finds Vittoria, so she’s soon amongst company again, though not by choice.

What Vittoria wants, what she truly yearns for, I submit, is solitude. If that’s the case, then Vittoria wants something she cannot have, something she herself has no language to ask for, because a woman who chooses to be alone is seldom spoken of and never heard. Her desire is not quite a secret, not quite a sin, but might be worse than both combined. In Vittoria’s life, because she’s beautiful, charming, alluring, to be alone would deny men their dreams.

L’Eclisse is often described as a film about loneliness. I almost agree, but that word, loneliness, is more diagnosis than description. We presume Vittoria is lonely because she’s often silent, chilly, and alienated around men; in fact, after she’s broken up with Riccardo, she’s merely alone. It’s in those scenes, before falling into the affair with Piero, that she seems most open to possibility, whether found in female friendship or among the clouds.

Piero, too, might desire solitude to a degree similar to Vittoria, but his ways of attaining it are at once more recognizable and more accepted. The energy he expends on his career as a stockbroker, for example, paints him as a hotshot. He’s important to his boss, he’s admired or envied by his colleagues, but he’s not intimates with them. In one scene, he rushes away from work to meet a call girl—notice the approving, admiring glances from his fellow brokers—but tells her to leave when she arrives with dyed hair. It suggests Piero manages his human contact carefully, transactionally, and will forego contact when his control is challenged. By the end of the film, Piero can be assured that Vittoria won’t fawn over him, or be impressed by his new car, or halt her own life in service to his. She’s not a stock the broker will invest in, only gamble on.

We don’t know why Piero skips his rendezvous with Vittoria, but we know it’s not because he’s lonely. Because of his gender, his place in the patriarchy, and his function in capitalism, his desire to be alone reads like commitment issues, or sewing wild oats. We assume Vittoria’s lonely because of her place in the patriarchy and function in capitalism, when she’s actually in search of a comfortable, nourishing solitude.

4. What They Get

What to make of all this as Michelangelo Antonioni’s film? He’s the director, after all, and co-writer of the script, and one of the godfather’s of the auteur school of filmmaking—he’s all but assured authorship of Vittoria and Piero’s story. As transcendent and luminous and encompassing as Monica Vitti and Alain Delon’s performances are, Antonioni remains the visionary. What vision does he create?

I can’t make the case for Antonioni as feminist. Though the auteur expands the male gaze to include at least the possibility a woman might prefer solitude to domesticity and/or sex, the gaze of Antonioni’s camera remains male unless his audience makes the effort to look differently. He spares Vittoria punishment for her disillusionment, and Piero bears an equal share of their dissolution, but that’s hardly even, when you think about it. Giving the man half the blame is not equal to sparing the woman punishment.

Perhaps a case could be made for L’Eclisse as a proto-neurodivergent narrative, and Antonioni as an early translator of autism spectrum/attention deficit hyperactivity disorders onto film. I mean, Piero can’t sit still. His overflowing energy, his willingness to let that energy overwhelm the rules when it suits him, and the way he thrives in the chaos of the Rome stock exchange as a result, read to me as adult ADHD on screen. His commitment to the moment as a decision-making schema, as opposed to following a plan—what one often calls trusting your gut—strikes me as the so-called disorder turned to personal advantage. Piero is good at his job because he can hold many thoughts in his head at once, knows how to change course on a dime, and has the energy stores to out hustle anyone on the exchange floor. His challenge, therefore, lies in the fact those career assets are obstacles to long-term, meaningful, personal, adult relationships.

Vittoria, on the other hand, responds with unbridled enthusiasm when something—a plane ride, for example—captures her attention. The rest of the time, she’s silent, or almost. She will not waste words on what cannot be known and understood unless pushed to do so—in which case, her statements are cryptic, perhaps even creepy, or else so detailed and long-winded no one else can follow. Whatever the case, speaking her neurodivergent mind leads to feeling alienated, significantly othered. Perhaps this is why she seeks solitude. Like so many on the ASD spectrum, the only place that makes sense, that seems in order, is the inside of our own heads. It’s not an accident that Vittoria works as a translator: with the completed text in front of her, her only job is to find the exact word that expresses most perfectly the original’s intent, a job that leverages the intensely focused, detail-orientated, borderline obsessive nature of autism in adults. We’re told little of Vittoria’s career, and see none of her work—thanks again, patriarchy!—but see these tendencies in her relationships with family, friends, and lovers. In personal contexts, however, such tendencies are not the advantages they must be in her work. Like Piero, what leads her to success and satisfaction in one context leads to failure and alienation in another, and neither character, as per their respective neurodivergences, can bridge the gap without risking something essential about themselves, something they have little choice but to protect.

Perhaps what makes me like these characters, and root for these characters, and hope beyond hope they’ll stick together, even though the film practically tells me they will not the first time they meet—remember that scene with the column, Piero standing confidently exposed on one side and Vittoria half in hiding, peeking out from behind the opposite side of the column?—is that I believe they could help each other. With time and commitment, Piero and Vittoria together could compliment the other, creating as a couple a power they lack apart. But I’m on the ASD spectrum. My wife’s impacted by ADHD. Of course I’m going to root for Piero and Vittoria.

I suspect one of the reasons Antonioni’s ending sequence seems so perfect, so universally profound, is that it is itself a kind of neurodivergent expression. Images gain coherence through context and repetition. Speaking the unspoken, on the ambiguous dissolve of what’s been happening, with crystal-clear non-language. Explanation is self-evident and therefore unnecessary. Yet there’s endless pleasure in breaking it all down, and breaking it down again, in search of the exact, the knowable, the true. To find someone who will search with you—that’s lucky, and love, and in L’Eclisse, lost.