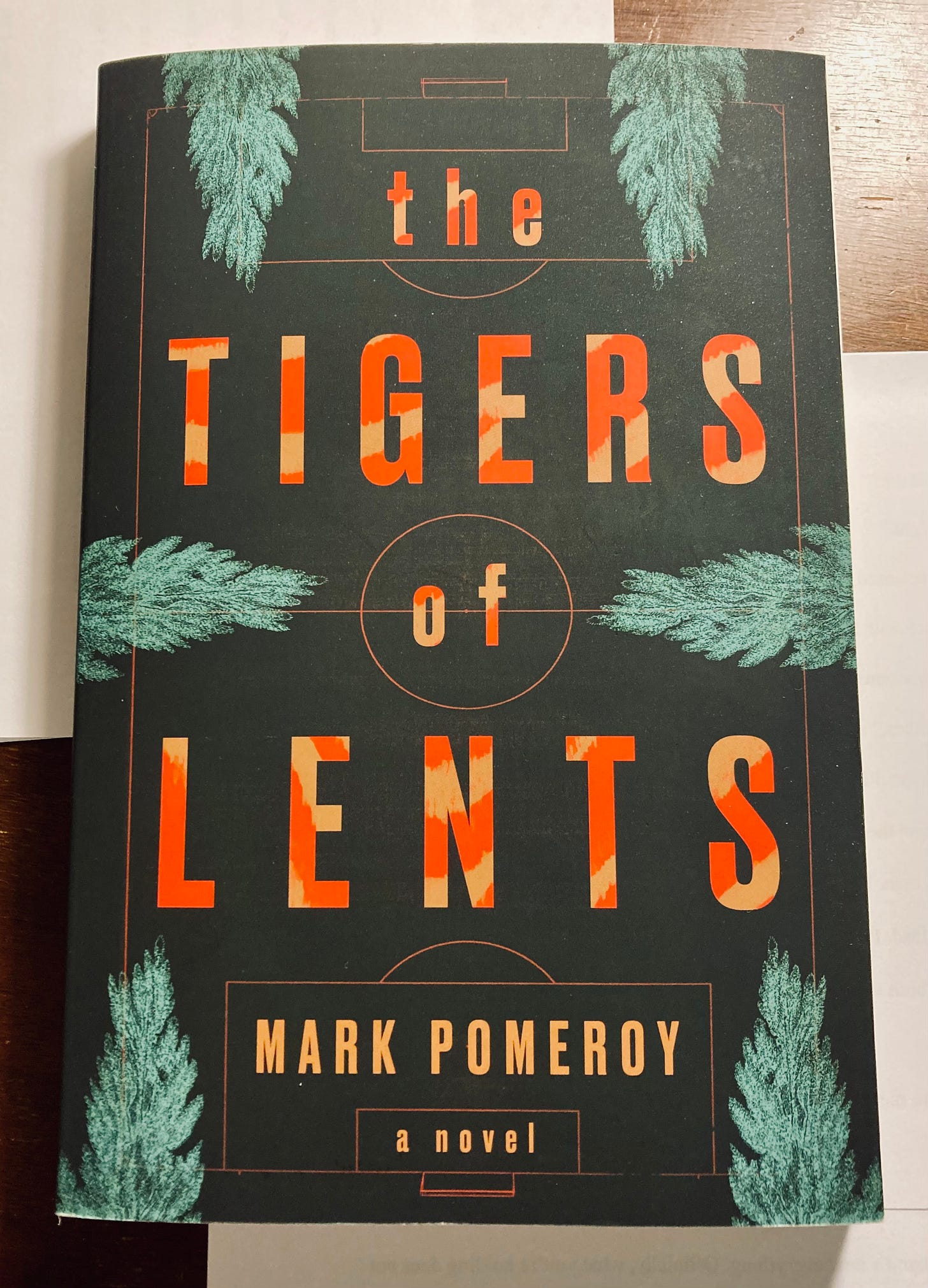

Last week, I read Mark Pomeroy’s new novel The Tigers of Lents (The University of Iowa Press 2024). For two days, I didn’t want to stop reading. I put the book down only when I had to, usually to eat or go to work, and even then kept thinking about the Garrison family. It’s been awhile since I last felt this way about a novel. In this John Carr Walker Sitting In His Little Room, I want to think about how and why The Tigers of Lents kept me invested, enthralled, happy.

The Home Team

I root for the characters. When they falter and fall short, I’m disappointed in them, and get a little angry with them, but keep rooting for them. You know how it feels when a favorite team loses a game they should have won? Or when the promise of a great year fizzles and fades through the season? When you have to rebuild your hopes around next year’s team? And yet, despite everything, you know your hopes will fly as high as ever? That’s what it feels like watching main character Sara Garrison.

Sara’s a soccer player, star of Marshall High School’s team, perhaps a soccer prodigy. Her talents on the pitch seem to come from nowhere: not from her parents, not from her local resources, and not from hard work. Sara’s mom is a cashier in Fred Meyer’s. Her dad’s in jail. She’s lived her whole life in the poor, far-flung neighborhood of Lents, in Portland, Oregon. It’s rough, potentially dangerous, like a dud firework or pounding storm. Signs of things changing are everywhere, but change is treated with suspicion. The people of Lents are fatalistic—like you learn to be, when every small good thing that enters the neighborhood is followed by a big bad thing. There’s a new cafe recently opened, but Marshall High School is closing. Sara will be in the last graduating class, and her younger sisters will have to go somewhere else, but there’s somewhere nearby selling nice lattés.

Sara fits right in to all of this. She’s one of them. A part of it. And Sara knows it, feels it, with all that entails. She gets by on grit, but she’s not determined. She’s precociously talented and precociously self-sabotaging, cruising, drinking, and smoking away her time, her chances, and maybe, her talent. She’s devoted and loyal, intensely so, but all that devotion and loyalty can turn to poison in the veins—and to venom on the tongue—when she’s let down or betrayed. No one’s better at letting down Sara than Sara.

And yet, I believe in Sara’s talents, her precociousness and prodigy-like status. I need to, because if I don’t, the novel’s story-altering event would seem like fantasy. She’s offered a scholarship to The University of Portland. When that offer’s made, the reader must believe that Sara deserves her chance, even when Sara does not believe it. And even though it takes Sara a painfully long time to claim her place at UP, we must keep rooting for Sara, the way we root for the home team, even though we’ve learned well her capacity to break our hearts.

Offense and Defense

I usually read short stuff, stories and essays and poems and what I like to call “poetic novels”—short books that elevate the lyric, bury the plot, and build toward moments of clarity that will cast the story in new light. Lydia Davis, Silvina Ocampo, Yu Miri, Yuri Herrera, to name a few.

The Tigers of Lents is not like that. Pomeroy’s writing is in service to the the story and plot, the characters, and their perspectives. The third-person narrator is forthright and honest. When the voice slips into a character’s thoughts—Sara’s, one of her sister’s, or her parents’—the rhythm and diction of the prose changes only slightly. The voices that make the characters distinct individuals, and the collective voice that ties the characters together, are closely related.

As a writer, I was raised on this style, so to speak. The narrative voice in service to the story dominated my graduate school reading. But sincerity begins to cloy after awhile. What’s more, I began to recognize the fact white male writers are often praised for being clear and forthright—for telling it like it is—but women writers and writers of color are attacked for their clear, forthright styles, as if telling their experiences like it is threatens reality itself. The more I pushed myself to read outside my gender, sexuality, ethnicity, nationality, and native language, the farther away from forthrightness I moved.

Pomeroy, however, gets away with it. I don’t use the phrase pejoratively. He tells the story of a soccer prodigy (I use the word “prodigy” carefully in this context) with deep working class roots, her defeated mother, jailed father, and flailing sisters using a clear, forthright narrative voice. He uses his privilege (again, careful) to help us root for, suffer with, and celebrate characters not typically afforded the space to tell it like it is, much less the luxury of authority.

Home-Field Advantage

Sara’s soccer scholarship brings her to the University of Portland, which is where I teach in real life, and where Mark Pomeroy went to school as an undergraduate. It would be a mistake to discount the importance of this common ground, shared between me, the author, and the main character. A kind of communion happens between reader, writer, and character when a familiar place is rendered perfectly. I recognize every detail in Pomeroy’s descriptions of campus and my own senses fill in the rest. I suspect, as a result, I trust his descriptions of Sara and the Garrison family all the more for it.

That said, I feel I’ve met Sara, too. I’ve only driven through the neighborhood of Lents, but since finishing Tigers, I’ve been seeing Sara in my neighborhood of Saint Johns, and remembering neighbors from my old haunt of Saint Helens, former students from Fresno and Kerman High Schools, classmates from Alvina Elementary I haven’t thought about in forty years—people with few economic and social advantages, but with fierceness on their side, and if they’re lucky, a precocious talent. And of course, I see see Sara among my students.

Yet they look to me like the Sara who’s easy to root for. They’re showing up. They’re in class, at practice, engaging with friends, coaches, professors. Pomeroy’s novel reminds me none of it’s as simple or as easy as it looks.

As The Tigers of Lents so powerfully and plainly dramatizes, the struggle to rise above what you thought yourself capable of, to be more than what a hard world teaches you you’re worth, features at least as many struggles as triumphs. A professor like me can confuse those struggles with excuses. Sara Garrison reminds me to root for my students. That’s easy when they do great things—I must remember to root for them when they don’t do great things.

News flash! My micro-fiction “Late Strathmore” was published this week in Sophon Lit Issue 5: Mirage. Follow the links to read my story and the whole beautiful issue. —JCW